Harvest in Photos

Learn about the history of harvest in Ulster with Senior Curator of History, Victoria Millar.

Lammas Day

The harvest season traditionally began on Lammas Day at the start of August.

In Ballycastle, a Lammas Fair has been held on the last Monday and Tuesday in August for almost 400 years. Lammas Day is also known as Loaf Mass Day. The name originates from the word "loaf" in reference to bread and "Mass" in reference to the primary Christian liturgy celebrating Holy Communion. It marks the blessing of the First Fruits of harvest.

The Potato Harvest

Potatoes are grown from the shoots that sprout from the ‘eyes’ of seed potatoes. Potatoes are usually grown in drills. These make weeding and spraying of the growing plants easier, and ensure the tubers are well covered with soil. If the tubers are exposed to sunlight they will develop green patches. The potatoes are mature and ready to harvest when the green tops die back.

The potato harvest occurred between August and October when the potatoes were mature and ready for picking. After the potato digger had opened the drills, the potatoes were picked or ‘lifted’ by hand. This dirty and back-breaking job was often done by teams of boys and young women. So many children took this chance to earn some money that country schools would close for a few weeks in late Autumn. Once they had been picked, the potatoes could then be washed.

Having been washed, the potatoes were taken home to be eaten or to market to be sold.

Depending on the abundance of the crop, some potatoes could be ‘clamped’ using straw and soil. This was an efficient and cost-effective way of storing potatoes that weren’t immediately required.

Potatoes matured at an opportune time, providing vital sustenance for those who were working elsewhere on the land.

Harvesting Hay

Hay is grass, cut, dried and stored, and used to feed animas such as cattle, sheep and horses during the Winter months when there is not much grass to graze in the fields. Farmers grew hay mostly to feed their own animals or for sale. The grass was cut around July/August when it was just about to flower, and at its most nutritious. It had to be dried as quickly as possible (a process called ‘shaking out’), to retain its food value. The next step was to rake the partially dry hay into rows.

The hay was then carried and raked into small heaps. These could be spread out and remade over several days until considered dry enough, and then made into a rick, or larger pile of hay.

The hay was made into a stack which was built up with straight sides, or outward leaning sides, for several feet. Then the steep conical roof was formed. This was thatched with straw to make it water tight. Several days of warm dry weather was essential for haymaking. Repeated soaking with rain reduced the nutritive value of the hay, and damp hay rotted and was useless.

The Hay Harvest

Harvesting Grain

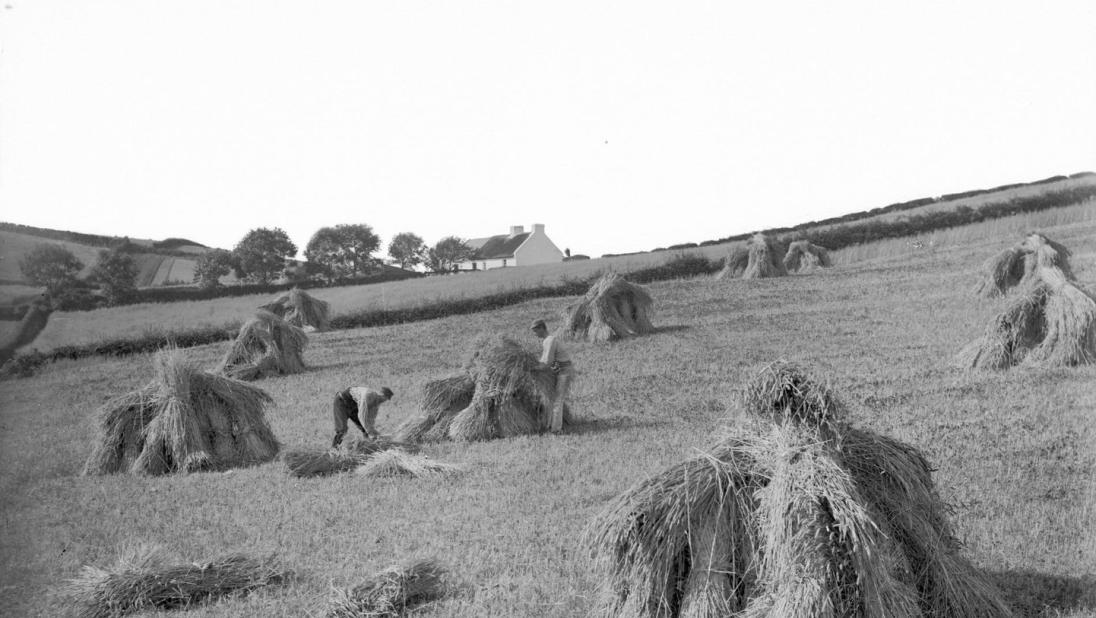

The harvesting of grain largely occurred in August and September. Until the late 19th century, most grain harvesting was done by hand, using reaping hooks and sickles. The reaper grasped a bundle of stalks in one hand and cut it with the blade held in the other.

Later, horse drawn reapers were used. Binders followed behind, tying the cut grain into sheaves. The sheaves of grain were made into stooks to dry, and then into stacks, ready for threshing.

Threshing grain is the process of removing the seeds from the straw. The simplest machine for doing this is the flail. A flail is made of two sticks, about three or four feet long, tied together. One stick is held, and the other is used to beat the seed out of the sheaf, which was placed on the ground at the worker’s feet. One man could work alone, or up to four could work together, building up a rhythm.

The Grain Harvest

Portable threshing machines consisted of a series of fluted rollers and beaters that knocked the seed from the grain and separated out the straw. The grain was poured into sacks, and the straw gathered up to be made into stacks. They were large machines, powered by steam engine (later by linkage to a tractor) and were hired, often by groups of farmers.

Cutting the Last Sheaf

The cutting of the last sheaf was traditionally accompanied by a special ceremony called, “Cutting the Calacht”.

Once cut, the sheaf was often decorated and hung above the table at a celebratory harvest meal, called the ‘churn’ or ‘harvest home’.

Generally the sheaf remained in the home until the following harvest, when it was replaced by a new sheaf.

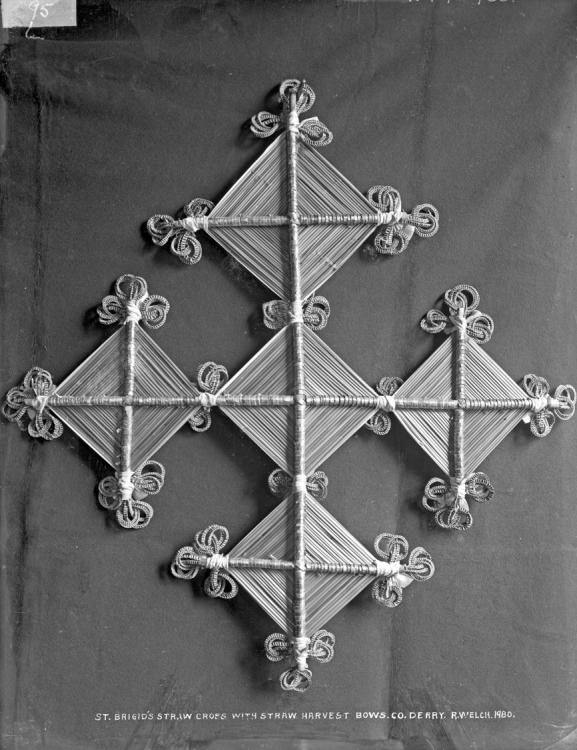

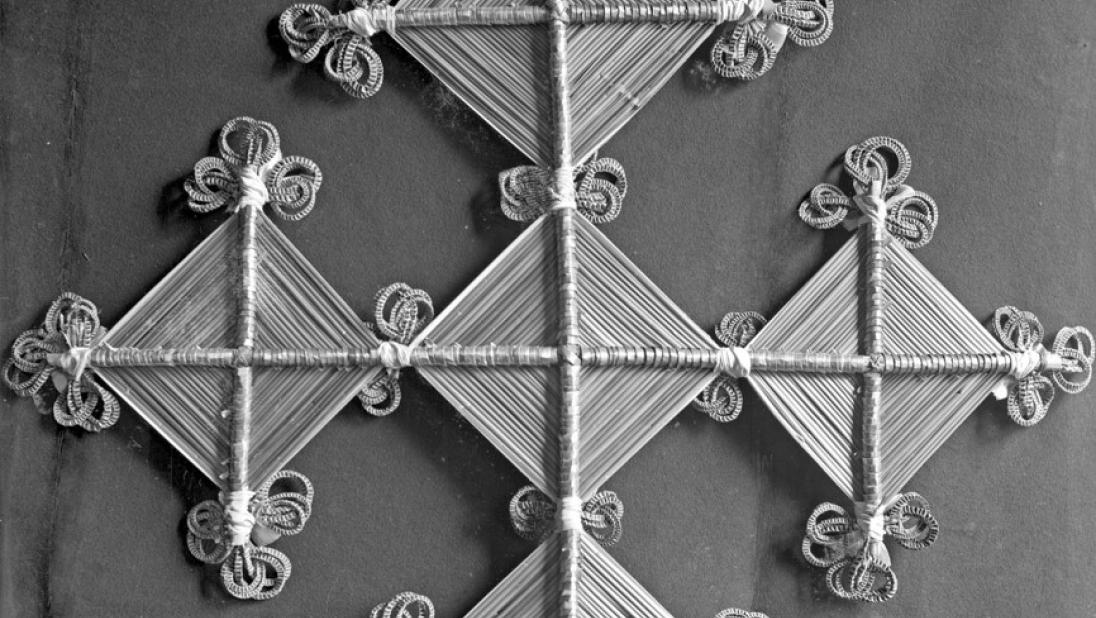

Harvest Knots

In some areas, as part of the harvest celebration, small ornamental twists or knots of plaited straw were made and worn as a sign that the harvest had been completed. The knots were based on a simple plait which was multiplied to make more complicated designs. Knots worn by young girls often had the head of the corn intact, symbolising fertility. Knots worn by young men were trimmed.

Although the production of knots deteriorated in the early twentieth century, many older members of the community still made knots for the younger harvesters to wear.

Designs could be very elaborate, like this straw harvest cross with bows.

The end of harvest meant that preparations for next year’s harvest could begin.